?All my thoughts are directed towards England. I want only for a favourable wind to plant the Imperial Eagle on the Tower of London.?

Once again England faced the threat of invasion and, with Napoleon massing an army of some 130,000 troops and 2,000 boats on the French coast near Boulogne, thoughts turned to how to defend the Romney Marsh - a low-lying stretch of coast which was expected to be the landing point for any French invasion.

Defending the Marsh

The Romney Marsh had been left virtually undefended in the belief that it could be quickly flooded and the subsequent morass, criss-crossed by drainage ditches, would be impassable. The very real threat of Napoleonic invasion led to questioning of this long held view. After much deliberation Lt-Col John Brown, Commandant of the Royal Staff Corps, rejected it as unworkable, concerned by the need for ten days advance warning and the potential embarrassment, chaos and huge expense that would result from a false alarm.

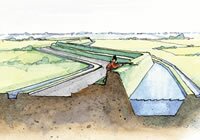

Brown had another idea. He suggested that a canal be built from Seabrook, near Folkestone around the back of the Romney Marsh to the River Rother near Rye, a distance of 19 miles. The canal system would have sources of water from the sea and the River Rother. It would be 19 metres wide at the surface, 13.5 metres wide at the bottom and 3 metres deep. The excavated soil would be piled on to the northern bank to make a parapet, behind which troops could be positioned and moved out of sight of the enemy. The canal would also have ?kinks? to allow enfilading fire along the length of the canal, if the enemy attempted to cross it.

The Duke of York and the prime minister, William Pitt, met on September 26 1804 to discuss the project: they were enthusiastic and preliminary plans were quickly made. The renowned engineer John Rennie, whose previous projects included the construction of London and Waterloo Bridges, was appointed as consultant engineer and it was proposed that the canal be extended from the River Rother to Cliff End, East Sussex incorporating the River Brede in the process. The total length of the canal would be 28 miles, of which 22.5 miles had to be dug. It was estimated that it would be completed by June 1805 and cost £200,000.

All that remained was to convince the local landowners of the advantages of the scheme. Pitt met with the landowners on October 24 at the New Hall, Dymchurch and explained that the canal would not only help to defend their country but would be a major drainage system for the winter, and a reservoir for the summer and would greatly improve conditions on the Marsh. They were persuaded. Pitt was popular with the locals, who referred to the canal as ?Mr Pitt?s Ditch?.

Digging the Ditch

On October 30 1804 the first sod of the Royal Military Canal was dug at Seabrook. Harsh winter weather and severe flooding, as well as difficulty in attracting labourers - known as navvies - meant that the original completion date appeared wildly optimistic. Frustrated by the lack of progress, Rennie blamed the incompetence and greed of the contractors, accusing them of overcharging and poor supervision. By May 1805 the canal project was close to disaster: only six miles had been completed and work had stopped. William Pitt intervened: the contractors and Rennie were dismissed.

The project was put in the hands of the Quartermaster-General?s department with Lt-Col. Brown in command. Navvies dug the canal, while the military built the ramparts and turfed the banks. Flooding continued to be a barrier to progress and hand pumps were used day and night to keep the trench from filling with water. Eventually powerful steam-driven pumps were used to clear the water.

At its peak there were 1,500 men working on the canal. The canal was dug entirely by hand, using picks and shovels and the soil was carried away in wheelbarrows. Once the canal was dug it was lined with clay. The change of command and the greater work force speeded progress so that by August 1806 the canal was open from Seabrook to the River Rother. However, concessions were made. The original dimensions of the canal were greatly reduced due to increasing problems encountered by the builders and pressures of time, so that for most of its length the canal is half its projected width.

Iden Lock was completed in September 1808, which linked the canal to the River Rother and Rye Harbour, effectively turning the Romney Marsh into an island, but it wasn?t until April 1809 that the canal was actually completed

After Napoleon

By the time the Royal Military canal was fully ready for use, the threat of invasion had long since past. Napoleon?s plans for invasion suffered a major setback following his navy?s defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. He withdrew his troops from the French coast and focused his intentions on central Europe.

The fact that the canal was never used for its intended purpose, cost £234,310 (a huge amount in Georgian England) and was funded entirely by the state meant the voices of cynics and doubters could soon be heard from all sections of society. The canal became an embarrassment to the Government - it was considered to be a white elephant of the largest proportions and a huge waste of public money. The radical journalist William Cobbett, who toured the country on his Rural Rides during the 1820s, was typical of the critics of the canal: ?Here is a canal made for the length of thirty miles to keep out the French; for those armies who had so often crossed the Rhine and the Danube were to be kept back by a canal thirty feet wide at most!?

The Government desperately needed to find ways of recovering some of the money spent on the canal and in 1807 opened it to navigation and collected tolls for the transportation of produce and goods. In 1810 the canal was opened for public use and tolls were also collected for the use of the military road between Iden, Rye and Winchelsea. There was also a regular barge service running between Hythe and Rye, which took around four hours to complete.

Despite efforts to utilise the canal, traffic was never heavy, and the opening of the Ashford to Hastings railway line in 1851 further decreased its use. The Government was struggling not only to recoup the money invested in the canal but to meet the ever spiralling costs of maintenance. Thus, during the 1860s the Government took steps to unburden itself from the canal. The stretch from Iden Lock to West Hythe was leased to the Lords of the Romney Marsh for 999 years at an annual rent of one shilling, while the the town of Hythe purchased the remaining stretch, that ran through the town, for conversion to ornamental waters. The canal west of Rye was sold to four individual owners. By the late nineteenth century the canal trade had all but gone. The last ever toll was collected at Iden Lock on December 15 1909.

Despite previous doubts surrounding the canal?s usefulness for defence in the nineteenth century, it was quickly requisitioned by the War Department in 1935 as war in Europe became increasingly likely. The banks were lined with pill-boxes as the nation awaited invasion, this time by Hitler, but once again there was no invasion.

The Canal Today

Although never being called upon to defend the nation, the canal has fulfilled one of its intended duties: the improvement of conditions on the Romney Marsh. The canal acts as a sink for the network of ditches that criss-cross the Marsh. During the summer, when rainfall is low and water is needed to irrigate the land, water is pumped from the canal into the drainage ditches. In winter, when there is a risk of flood, water can be taken from the ditches into the canal and the excess water let out of the canal at Iden Lock or the sluice at Seabrook. This vital function of the Royal Military Canal is managed by the Environment Agency.

Today the tree lined banks of the Royal Military Canal are an excellent place for quiet enjoyment, whether walking, fishing or simply watching the world go by. This large stretch of fresh water provides a home for many forms of wildlife, and parts of the canal are designated as Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), with the remaining length designated as a Local Wildlife Site. The Royal Military Canal is also protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM), ensuring its survival for future generations.